It is not exactly an observation laced with uncommon insight to say that the political discourse in this nation has degenerated to a place maybe unknown in living memory.[1] Complete discord and disunity. Unbridled animosity. Hypocritical intolerance. Often baseless accusations. Rash condemnation. Outright hatred. Death wishes via celebrity Twitter accounts. Death threats. Attempted murder in Alexandria, VA. Murder in Charlottesville, VA.

Incomprehensibly, the church of Jesus Christ – the church presumably built on His self-sacrificial example and His commandment to love, bless, and pray for even our enemies – finds itself deeply embedded in the fray and cacophony of this radically divided social and partisan decay. It finds itself openly aligning with and pledging to political parties and politicians, pushing legislation and policy preferences, seemingly fully reliant on the power of government to save, and fully invested in what appears to be nothing less than a “winner-take-all” conflict.

The prize is a sociopolitical environment altogether hospitable to the victors, but deeply hostile to the vanquished. There is no 2nd or 3rd place. There are no silver or bronze medals in this contest. For the various and sundry players on the field, seemingly everything is at stake. Some on the ragged edges of the conflict even assert that the difference between winning and losing will be a matter of life or death before all is said and done. Some feel that it already is a matter of life and death.

But what do the scriptures have to say to the church about our place, our role, and our participation in this contemporary political and cultural maelstrom – or any other across the timeline of history?

Is the call and responsibility of the church to become an activist group, lobbying and legislating on behalf of the kingdom of God (or at least on behalf of our “God-given rights”)? Or should we take up Rod Dreher’s controversial Benedict Option?[2] Should we adopt a flexible posture of general conformity, re-tooling our message and approach in a more “culturally relevant” and “seeker sensitive” fashion? Or should we simply hold the fort, praying for Jesus to return, embracing a growing insularity while exhibiting an increasingly passive-aggressive response toward the world around us?

This is the first in a series of articles explaining my ever-evolving thought on what the scriptures actually have to say about the relationship of the church and its members to the state and the forces that animate it. Laying my cards on the table up front, I believe that there are some things we are not seeing clearly about the nature of this relationship. I believe that the Bible, in both very direct and indirect ways, has given some valuable instruction to guide us, to lead us, and, yes, even to caution us in the way we interact with these forces – especially when the attempt is to use them to bring about God’s kingdom imperatives.

First, this is not another diatribe by a former Conservative Christian who has seen the error of his ways. It is not another repentant confession by a misled Evangelical who has now embraced the progressive values of Social Justice and other left-leaning interpretations of the gospel. Nor is it an “I’ve seen the light” reversal by a former progressive who has come to see in the gospel an endorsement of distinctly American values (democratic, economic, or moral).

There are plenty of those kinds of stories out there. But in my case, I have not simply exchanged one political outlook for another. I am, however, learning what it means to exchange one kingdom for another. What this actually means is something I hope to make abundantly clear as we go.

Second, everything I will have to say in upcoming entries applies to both the left and right-leaning factions in the church, equally. This is because, while the kingdom of God shares certain similarities with conservatism (usually moral) and progressivism (usually social), it is actually neither of them. It is not even what we often refer to as a “third way.” The kingdom of God is completely other, and it exhibits a stubborn and persistent refusal to be co-opted by the multitude of terrestrial forces that would use it to accomplish their own ends.[3]

An important part of laying the groundwork for this series is clearing the air of certain assumptions about what I am saying before we engage – assumptions that even now might be fomenting in the mind of the reader. Maybe the most important thing to address at the outset is what I am not saying.

- I am not saying that we should disengage the world and enter into retreat.

- I am not saying that we shouldn’t be informed about what is happening in the world around us.

- I am not saying that we shouldn’t have very strong opinions about political developments, especially when they directly impact us and our loved ones.

- I am not saying that we shouldn’t exercise responsible and conscientious civic participation.

- I am not saying we shouldn’t speak to the issues, especially those which threaten the well-being of humanity.

What I am saying:

- We must learn to differentiate between that which is of the world and that which is truly representative of God’s kingdom.

- We must learn to differentiate between that which is flesh and that which is Spirit.

- We must learn to lay aside the personal agendas and coercive tendencies that always attend the ways of the world and the flesh, even when that costs us a great deal, and even when we have within our grasp the power to establish our goals through political means.

- We must learn that the goals and imperatives of the kingdoms of this world generally stand in stark contrast to those of the kingdom of God. In the rare instances in which they overlap, they do so coincidentally and quite superficially.

- We must understand God’s attitude toward these earthly and temporal powers because it is unmistakable: “The kingdom of this world has become the kingdom of our Lord and His Messiah, and He will reign forever and ever.”[4]

Ultimately, I am saying that the goal, the task, the responsibility, the passion, and the singular strategy of the church should be to express, exhibit, represent, and demonstrate God’s kingdom in love, in purity, in power, and in truth, until its final and complete arrival – a day that will see it overthrow every other competing kingdom and establish its reign forever. I am saying that this route is the only one that has any genuine power to affect real and lasting change in our nation or in the world at large.

As a method of being consistent and concise, we will be using two phrases throughout this series:

- The Kingdom of God

- The Kingdoms of this World

We will delve deeply into the meaning of both, but for right now, let’s provide a preliminary working definition of each:

The kingdom of God refers to the realm from which God rules and reigns. It is a realm whose inauguration on earth was announced with Jesus Christ’s arrival. With the coming of the Messiah, a new declaration was made to the world: “Repent, for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.”[5] Jesus was the embodiment and perfect revelation of that kingdom.

The kingdom of God is a realm in which God’s will is done perfectly.[6] Jesus says that this kingdom currently lives within and among his followers even now, displayed wherever they go.[7] And this kingdom is yet destined to supplant every other kingdom[8] and establish its universal reign forever.[9]

The kingdoms of this world refer to the various global authorities and powers which vie for control and domination of the earth (whether that domination is local or global in its ambition).

These powers include the nations and all of the political and governmental machinery that drives them. It also includes military strength, law, economics, commerce, arts and entertainment, etc. They also include the powers of darkness: Satanic and demonic forces.[10]

Moving forward, whenever we refer to the kingdom of God, we are referring to the realm of God’s rule – which is both here now but also yet to come (in terms of its fullest expression).

When we refer to the kingdoms of this world, we will be speaking specifically about the political and governmental expressions of those kingdoms, the human forces that steer them, and the evil powers that manipulate them from behind the scenes.

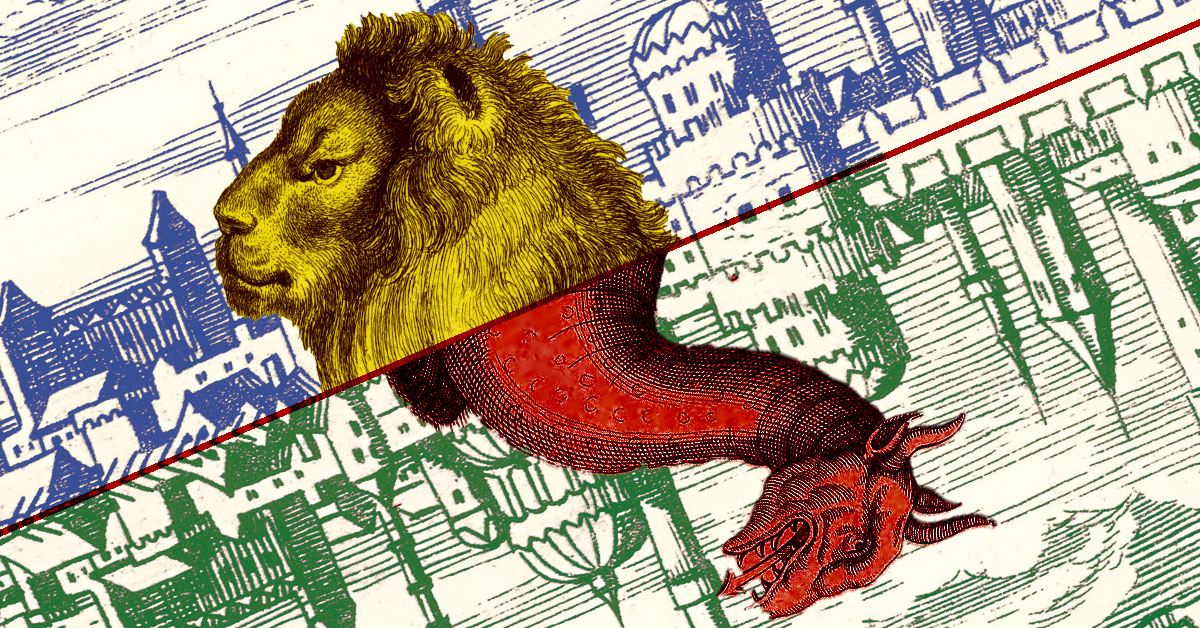

Theologian and pastor Greg Boyd[11] succinctly and effectively contrasts these two kingdoms this way: “While all the versions of the kingdoms of the world acquire and exercise power over others, the kingdom of God, incarnated and modeled in the person of Jesus Christ, advances only by exercising power under others.”[12]

Boyd goes on to explain that the power under of the kingdom of God is best symbolized by the cross, while the power over exercised by the kingdoms of this world are best symbolized by the sword. Truth, love, service, and sacrifice versus selfish ambition, coercion, and force.

Which set most immediately stands out as being the most accurate description of God’s kingdom?

The essays which follow in this series do not unfold in any particular order. They are not a systematic treatment of the topic, because the scriptures are not systematic in the way they address it. I will not be attempting to build an argument for “my position,” as much as I will be seeking to provoke deeper consideration of certain conclusions often taken for granted in the church today – particularly the American church. These articles represent a collection of thoughts aggregated over time, as I have sought to navigate the maze of my position as an appreciative and grateful American citizen, juxtaposed with the fact that, as a Christian, I have a higher allegiance and loyalty to which I am bound.

Whether you agree or disagree with my conclusions, I hope these entries will have the final combined effect of deepening our allegiance to the only kingdom destined to remain forever – the kingdom of God.

[1] Some might argue that the current schism in this country was rivaled in the 1960s, citing the youth counterculture, anti-war protests, battles for civil rights and racial equality, and a new phase in the evolution of activist feminism. But based on my listening, many who were there suggest that a much stronger sense of genuine acrimony exists today. In the 1960s there was still a more or less unified sense of our national values, fading though they were. The indication is that in the 1960s the battle was for the full realization of America’s promise – even while significant numbers of young adults were beginning to question the value and validity of that promise. It was tense and at times even violent. Today, agreement about those national values has all but evaporated – resulting in a tangible and qualitative difference between upheavals in the 1960s and those in America circa 2019. We now clearly live in two different Americas, each one having fully decided on the evil embodied by the other. The fight is not always as overt and visible as it was in the 1960s, but the stakes are higher. We are caught in a vortex of competing and completely contrary ideas regarding what America will become. Some have likened it to a “Civil Cold War,” or a “Civil War by Proxy.” These proxies consist of various in-groups, special interests, political parties, and social movements vying for ultimate control – the power to impose and enforce their own definition of America with little regard for the democratic processes we on which we were founded.

[2] Rod Dreher’s Benedict Option is a proposal which focuses on (quoting the author), “Forming Christians who live out Christianity according to Great Tradition,” a task which, “requires embedding within communities and institutions dedicated to that formation.” Dreher’s proposal has been deeply criticized as a full retreat into a kind of 21st-century monasticism. This is a criticism Dreher rejects, and I think his reasons for rejecting that critique are good. I use the term simply because it has become somewhat synonymous with the idea of a functional Christian disengagement since the book’s publication in 2017. For more information see Dreher’s Benedict Option FAQ.

[3] It may appear to have been co-opted at various times, for example by modern political action groups like the Moral Majority on the right or activist ministries like Sojourners on the left. Or Constantine’s Rome, as an ancient example. One must realize that man’s declaration that he is on God’s side has little bearing on whether or not God has declared Himself to be on man’s side. God calls man to be His representative. He doesn’t answer to us, that He should be our representative. Jesus Christ did represent man “once for all” through the sacrifice of Himself – but as an offering for our sin (Hebrews 7:27). Not as a spokesman for any political or social agenda. He represented us as a substitutionary atonement, dying in our place as a sacrifice for the crimes we had committed against God. (Romans 3:10-26)

[4] Revelation 11:15

[5] Matthew 3:2; also Matthew 4:17

[6] Matthew 6:9-10 – “Pray then like this: ‘Our Father in heaven, hallowed be your name. Your kingdom come, your will be done, on earth as it is in heaven.”

[7] Luke 17:20-21 – “The kingdom of God does not come with your careful observation…for behold it is in your midst.” (“…for behold it is within you.” KJV)

[8] Revelation 11:15, as quoted previously.

[9] In the Book of Daniel, chapter two, Daniel the prophet interprets a dream experienced by Nebuchadnezzar, the king of Babylon. In his dream, the king witnessed a large statue made of gold, silver, bronze, and iron, with feet of mixed iron and clay. Daniel stated that these different metals represented different kingdoms and empires throughout history. Competing interpretations parse out the details differently, but Daniel makes it clear that the statue does represent various worldly kingdoms and their temporal authority (there is not much debate on this point). The vision ends with a “rock hewn from stone, but not by human hands” striking the statue on the feet, toppling it with such force that the shattered pieces are like dust blown away with the wind. The “rock” then becomes a mountain which grows to fill the entire earth. Regardless of one’s eschatological position, this rock is almost universally interpreted to be Jesus Christ, who will shatter all earthly power, setting up His eternal rule – which shall extend over all the earth.

[10] Ephesians 6:12 refers to them as, “The rulers, authorities, and cosmic powers over this present darkness; the spiritual forces of evil in heavenly places.”

[11] It is important for me to establish that my theological differences with Boyd are great, particularly regarding his Open View of God’s omniscience. My single quotation of Boyd should not be mistaken as a blanket endorsement of all he espouses.

[12] Boyd, Gregory A. Myth of a Christian Nation. Zondervan, 2005.